Scott Weingart discusses the basics of networks in his article, “Demystifying Networks.” He cautions that, “Networks can be used on any project. Networks should be used on far fewer.” Weingart warns not to apply networks to everything. He notes that network studies are made under the assumption that neither the information, nor the way the information relates to itself is the whole story. I began to have difficulty following the rest of the article at this point. As someone inexperienced with these terms, networks, 2-mode, bimodal, and multimodal sound like another language to me. And it is, a digital language. Weingart went on to stress,

“Besides dealing with the single mode / multimodal issue, humanists also must struggle with fitting square pegs in round holes. Humanistic data are almost by definition uncertain, open to interpretation, flexible, and not easily definable.”

Scott Weingart

He states that many in the digital humanities use or “borrow” networks from others, when these very same networks were creating to answer a specific question in a specific way. Weingart urges us that we “must be willing to get out hands dirty editing the algorithms to suit our needs.” This is sound advice, but I would have no idea where to start editing an algorithm. In the increasing use of digital tools and technology, many, in an attempt to “keep up” resort to borrowing a network, while also lacking the skills to alter it to suit their needs, or the parameters of their project. At times, digital humanities projects offer the illusion of speed and facility, but as we have learned this semester, that is not necessarily the case. From the very beginning of a digital project, there are a great many decisions to make, and these choices impact the success of the project. The careful organization of data, for instance, is one key factor.

Weingart gives a hypothetical example of a digital humanities novice falling into a particular trap. Newcomers will take a dataset, load it into their favorite software and visualizes it to create a network. At this point Weingart blames the ease of use of the software as well as the non-technical description of the buttons for what happens next. According to the author, the novice will press these enticing buttons to see what will come out. The trap is that the novice changes the visual characteristics of the network based on the buttons they have pressed. First of all, as a novice, I resent the implication that I am like a child with a toy, willy-nilly pressing random buttons. Second, even though I am a beginner, I would never assume that my curiosity about what would happen to my network if I changed some of the settings would lead to a scholarly conclusion. I am well aware of what I do, and do not know. It is not the fault of the software if the user is foolhardy in the conclusions she draws from it. Weingart seems to imply that the software should be more difficult to use, and the buttons more technological to impede a beginner’s use, so as to spare us from our ill-advised assumptions. Are we, or are we not trying to encourage more people (especially those in the humanities) to move into the digital arena? If the technology is too difficult to learn or use, then progress towards an acceptance of digital humanities projects will be very slow indeed. Would Weingart prefer to keep digital technology to only those with specific training in the field? If so, then why bother “demystifying” networks, which is an article clearly aimed at the beginner?

One project that we looked at this week was Orbis, the Stanford Geospatial Network of the Roman World, which is an interactive scholarly work (ISW). The viewer can plot a route anywhere through the Roman Empire as it existed in roughly 200 CE. You can see not only how long this journey would have taken, but also the route, and the expense, based on modes of transportation. You can even account for the season you will be traveling in. ORBIS is a website with both static and interactive components. I was amazed to discover that it only took nine months to build. The designers drew data primarily from the Pleiades project, along with route information from the Barrington Atlas. ORBIS would be a great educational tool for K-12. One of the advantages of DAH projects is how accessible they are to a variety of students. Everyone learns differently, and anything that makes information more accessible and/or more exciting is valuable.

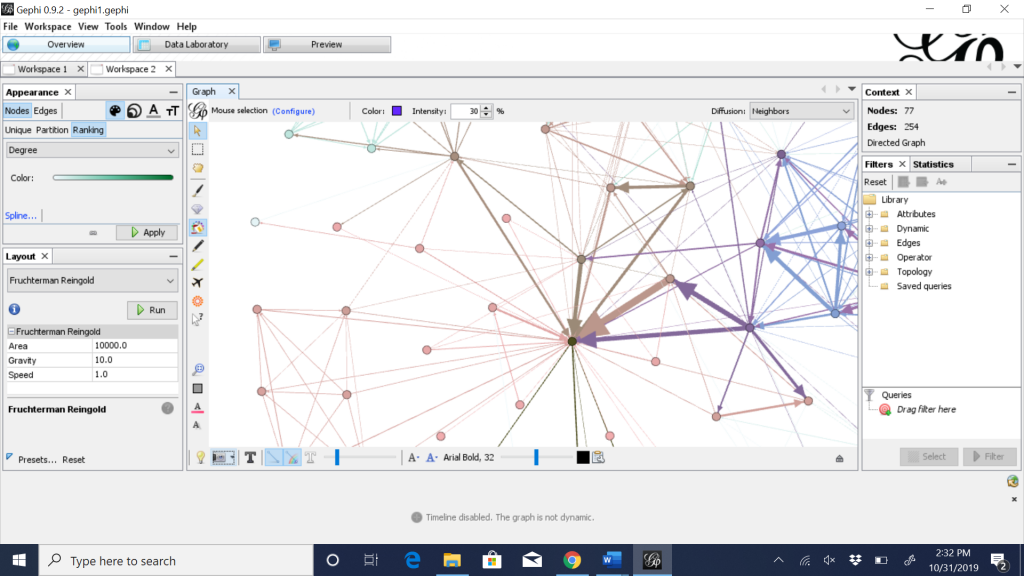

This week we worked with Gephi in class. Above is a screenshot of my network. I had difficulty in maneuvering the network image around (perhaps using a mouse would work better than a laptop?) but at least this gives you some idea of what it looks like.

Here are a few of the positives of Gephi:

- Gephi has a simple interface, and the tool symbols are logical and easy to find.

- The data import process is easy in CSV format.

- The software produces a graph automatically once the correct data is loaded and mapped together (edges and nodes).

- Customization. You have the option to change the size and color of nodes and edges to represent different characteristics of the graph.

The biggest negative for me:

- In Gephi, there’s not much of an export feature for the map you’ve created. Screenshots can be taken, but you can’t currently export to an image or HTML document. So, what do you do with it once it’s been created?

While only having a cursory experience with Gephi, I’m not sure I would want more. The difficulty in exporting the file is significant, in my mind. If you create a network, you would want others to be able to see it, not as a static image, but as a dynamic one. I admit to being biased against text-based analyses. I have always been a visual learner, and for me personally I prefer Storymap or TimelineJS.