Throughout the semester, one of the tends that continuously arises in our discussion is the idea of collaboration. One of the central tenets of scholarly production in the humanities is that of work authored by a single scholar. Unlike the sciences in which it is expected for there to be multiple people- multiple scholars, graduate student assistants, lab assistants, etc.- contributing to the final publication of a research article, the disciplines in the Humanities expect one singular author to produce the entire work. One of the integral aspects of the ‘gold standard’ of the scholarly monograph is the idea that there is only one author who wrote it. That is why, when thinking about the transition to digital art history, many scholars in the humanities were skeptical. How would projects open up in this collaborative manner? This focus on the single authored work often meant that those who contributed to a digital project, including librarians, IT specialists, graduate students, and others, were often not recognized for their labor.

This tight hold on the single-authored monograph has loosened a bit, though certainly not completely. The ‘gold standard’ Digital Art History article that we have talked about throughout this semester is, of course, “Local/Global: Mapping Nineteenth-Century London’s Art Market” by Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich. Not only are there two authors working together to produce this article, but they also acknowledge the work of those who helped create the tools that they used to develop the article. But what happens when collaboration goes beyond the work of multiple scholars or other individuals within the ‘Academy’? What happens when the collaboration brings in the public?

This question was the topic of our discussions this week. Mass collaboration with the public, or crowdsourcing as it is called, is an attribute of the digital world that has been increasing for the past few years. In the article “Digital Humanities and Crowdsourcing: An Exploration,” the authors offer a thoughtful definition for the term:

“Crowdsourcing is a type of participative online activity in which an individual, an institution, a non-profit organization, or company proposes to a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number, via a flexible open call, the voluntary undertaking of a task.”

L. Carletti, G. Giannachi, D. Price, D. McAuley, “Digital Humanities and Crowdsourcing: An Exploration,” in MW2013: Museums and the Web 2013, April 17-20, 2013,

Within this definition, crowdsourcing can span a variety of projects, both related to Digital Art History and those beyond its scope. One of the more common types of crowdsourcing is projects that deal with transcription. The New York Public Library, Tate Museum, and the Smithsonian Institution are all examples of cultural heritage institutions that make collections of material available to the public so that members of the public can engage with these materials directly. Additionally, this allows for more transcriptions to occur and the materials to (ideally) reach a wider audience.

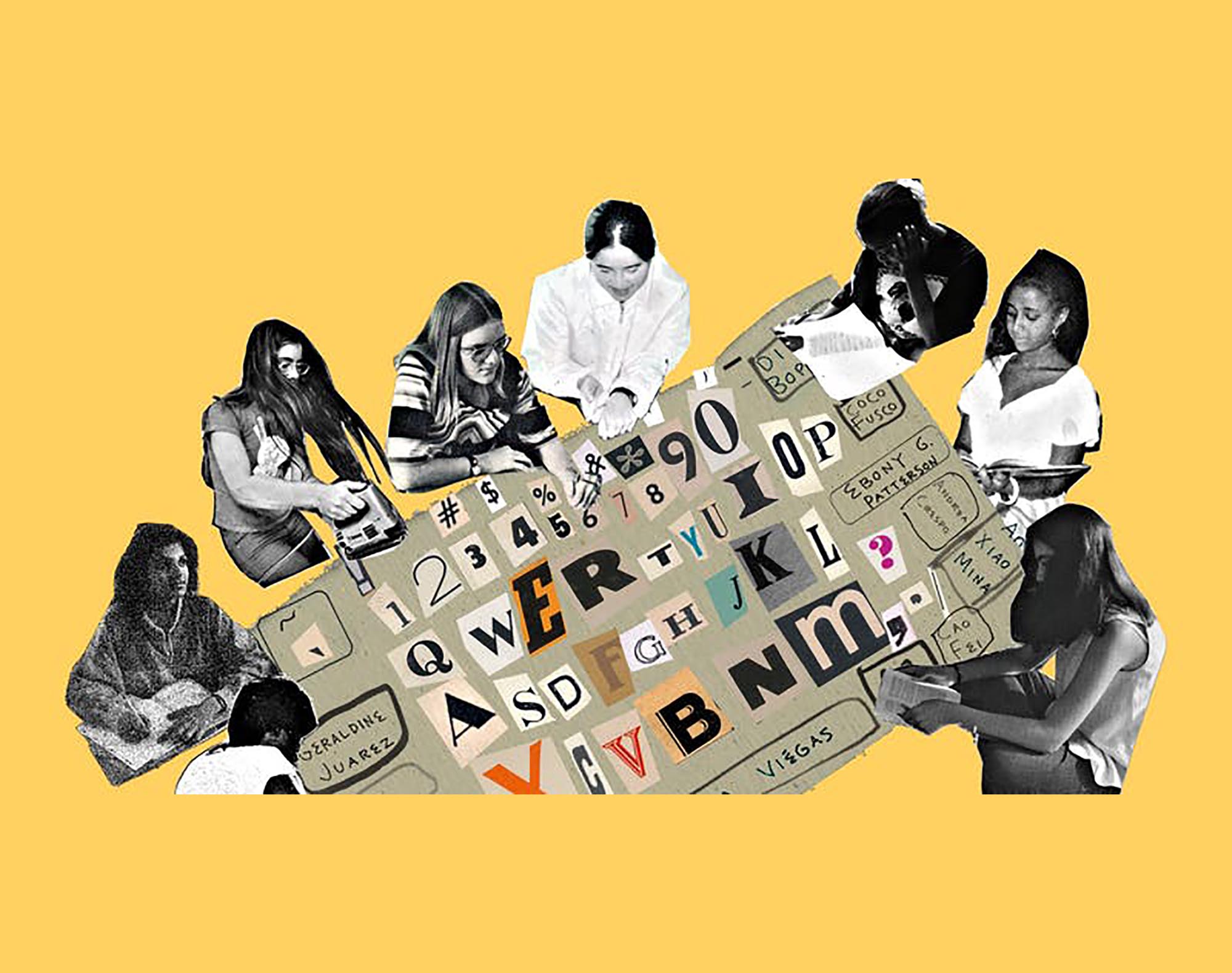

At first glance, at looking at these types of projects, the immediate answer that comes to mind (to the question: is crowdsourcing a good/positive thing) is often yes! It is engaging with the community, reaching a wider audience, and more work is ‘getting done.’ Yet the flip side to this line of thinking is- does the value of the professionals work (namely us, as art historians/ librarians/ museum professionals) become undervalued if we broaden these types of projects to the public? Will administrators think that our work can be done by just anyone with a computer if we open up these gates? Most of these questions arose when thinking specifically about our discussion of crowdsourcing exhibition curation, and are all valid questions. Instead of focusing on the negative aspect of crowdsourcing, for this blog post I wanted to focus on one of the positive resources or examples of crowdsourcing: Art & Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon.

For those who don’t know, Art + Feminism is an incredible, non-profit organization that is committed to increasing a diverse representation of the arts and art history. Their mission statement is as follows:

“Art+Feminism is a campaign improving coverage of gender, feminism, and the arts on Wikipedia. From coffee shops and community centers to the largest museums and universities in the world, Art+Feminism is a do-it-yourself and do-it-with-others campaign teaching people of all gender identities and expressions to edit Wikipedia.”

One of the aspects of their mission statement that I find particularly important is that of the people who are editing Wikipedia. Not only is the organization committed to editing or creating better representation of women artists on Wikipedia, but it is also committed to diversifying the population of those who edit. This mission stems from the fact that less than 10% of editors on Wikipedia are women. Ten percent! And the numbers only go down when you add in race and ethnicity.

One of the aspects of their mission statement that I find particularly important is that of the people who are editing Wikipedia. Not only is the organization committed to editing or creating better representation of women artists on Wikipedia, but it is also committed to diversifying the population of those who edit. This mission stems from the fact that less than 10% of editors on Wikipedia are women. Ten percent! And the numbers only go down when you add in race and ethnicity.

At this point, many of you may be asking, okay yes, this all sounds great- but Wikipedia? Haven’t we been taught for most of our life that Wikipedia is not a reliable source?

Well, yes and no. We still urge our students not to cite (or copy!) Wikipedia as a resource for their research papers, but how many times have we looked up a fact on Wikipedia? When was the Seven Years War? What’s the capital of Azerbaijan? Who was the twelfth president of the United States?

In an increasingly digital world, Googling someone’s name is often times our first step in researching their work. Admit it- we all use Wikipedia in our day to day life. I even use it as a starting point of research each page usually has an elaborate list of bibliographic sources.

So what happens if a student can’t find someone on Wikipedia?

What happens if a student is intrigued by a femme or genderqueer artist that they learned about in class and was interested in writing about them for their research paper, but when they Googled their name, nothing came up? Often times, that student will turn elsewhere, to look for a figure that is more well-known. Someone who has a Wikipedia page. Does this happen everyday? Probably not. But when it does happen, it continues the cycle of underrepresentation. For every article added, edited, or improved, more and more underrepresented people get their voices, and work, shown to a wider audience.

Is Art+Feminism’s Wikipedia Edit-a-Thons perfect? No, of course not. Just like in any other avenue of life, there are editors on Wikipedia that try to bring those woh are new to Wikipedia Editing down or remove pages that don’t completely follow the ‘pillars’ of Wikipedia. But overall, I think this is an excellent example of positive crowdsourcing. The results speak for themselves.

“Since 2014, over 14,000 people at more than 1,100 events around the world have participated in our edit-a-thons, resulting in the creation and improvement of more than 58,000 articles on Wikipedia. We’ve created and improved pages for artists like Tina Charlie, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Ana Mendieta, Augusta Savage, and Frances Stark.”