As promised, this Digital Art History Thursdays post is about the progress that has been made in my Modern Architecture course in using Google Map Engine Lite (now out of beta and officially My Maps) to create a group map. Phase one of the project will be finished in mid-October, but the following issues arose as we got started:

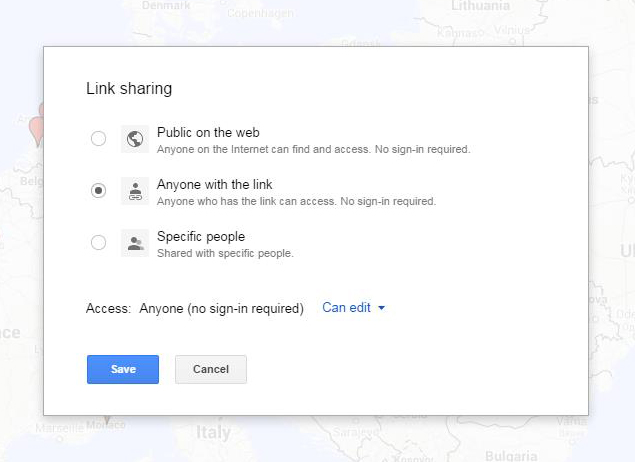

1. Google, in various ways, provides incorrect information about how to share maps in such a way that all users could edit the map. Below are the options that Google gives you for sharing maps.

Since our map was for class purposes, and would likely have some bumps along the way, option 1 was discarded immediately. The class will vote at the end of the semester about whether to make the final map public or not. In theory, I could have used option 3 to share with all of the students in the course by entering their individual email addresses into a list and letting them access the map by signing into Google, but this too was discarded as an option because Google rejected their university email addresses out of hand (and one at a time also–I would delete an email from the list and Google would reject another, and so on) and because the task of collecting everyone’s gmail address (and because some students did not have gmail addresses, which I did not want to force them to create) would have made the sharing process too piecemeal and drawn out instead of giving everyone equal access from the first day. So I chose option 2 and emailed the map link to all of the students via the course Sakai page–they could bookmark the link and Google (supposedly) wouldn’t care what email address they had or even who they were when they accessed and edited the map. Easy, right?

But then a student tried to access the map, and this is where things were clearly not as advertised. Notice above that option 2 says “no sign-in required” and that the access level is “Can edit.” My student could view the map, and could even see a red Edit button in the top right corner of the map toolbar on the left side of the map. However, clicking the Edit button resulted in nothing. Searching for a place in the map search bar would drop a green pin on the location, but that green pin could not be grabbed and added to the map. The student could, in actuality, not edit the map. Nowhere in the Google support documentation does it indicate that sharing maps requires signing in to Google before one can edit a map, but that is the truth that several independent help forums had conclusively discovered. Every student, even the ones who had not previously had gmail or Google accounts, had to now sign in to Google to be able to edit the map.

So Google lied. But it was more like they lied out of ignorance about how their own tool was supposed to work than to deliberately obfuscate. In theory, maps work like docs on Google Drive. In practice, Google’s My Maps can be viewed by strangers (to Google) but only edited by friends (of Google). Something to consider when looking for a more open tool for classroom use.

2. We also discovered that, despite the promise of the ability to add data to a map by importing it from an Excel spreadsheet, Google only allows one spreadsheet import per layer of the map. Out of general assignment fairness, I couldn’t allow the first student out of the gate to have this ability and then deny it to everyone else. This required a bit more logistical thinking before coming up with a procedure that could be used by the whole class.

I could have had each student make a layer, and, since I have a Maps Pro account, we would have been able to have that many layers (times 2, because the students would be doing the same thing for the next phase of the project), but this would also have been difficult to read through on the maps toolbar and also open up a lot more room for importing and data entry error (data columns in different orders from layer to layer, less accurate place locations found, etc.).

Or I could have had every student send me their spreadsheet data a few days in advance of the phase one unveiling and then I could have synthesized their data into one sheet and uploaded it to the map. Since part of the goal of the project is to have the students get hands-on with the digital tool, this was an obvious nonstarter.

So, instead of adding data in sets, each student will be adding individual points to the map for their assigned “section” of the project. Already we have seen that the map search bar can find built works at their actual physically specific street address, so the pins will be very accurately placed on the map, without the students having to enter GIS coordinates. The students can still copy and paste prepared data from their spreadsheets (which is the part of the assignment that will be turned in for the actual grade). And they can more directly and easily add images and video directly from the pin editing function using Google search. Since most students will be adding 15-20 pins, taking the route of adding one item at a time is not excessively burdensome as a whole.

For the next blog post, a report on the results of phase one of the mapping project.