In this week’s topic, we revisited the idea of mapping in digital art history, but this time focused on not only mapping space, but also mapping time. Of the digital tools that we have (and will) look at this semester, mapping time seems to be one of (if not the) most recognizable concepts. Creating timelines and chronologies is nothing new in the humanities, nor in history in general; people have created analog or even digital timelines for hundreds of years- is there a timeline for the history of timelines…? But I digress.

With the advent of new and ever changing digital technologies, there have been new and more interactive tools used to create complex timelines. In the realm of art history, the best known, and possibly most used timeline, is that of the Heilbrunn Timeline of the History of Art, hosted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Founded in 2000, the timeline is a comprehensive overview of the history of art and is navigable through a variety of ways and is a very useful and widely positively received resource. Moreover, it is an example of a resource that maps both time and geography. As such, I wanted to spend the majority of my blog post this week thinking about this timeline, and the project as a whole, in relation to the ideas of digital art history. My blog post will conclude with my own example of a timeline that I created using KnightLab’s TimelineJS. But first, let’s look at the Heilbrunn Timeline.

The project describes itself as such:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History presents a thematic, chronological, and geographical exploration of global art history through The Met collection. Authored by The Met’s experts, the digital publication is a reference, research, and teaching tool conceived for students and scholars of art history. The Timeline currently comprises more than 1,000 essays, 8,000 works of art, 300 chronologies, and 3,700 keywords. It is regularly updated and enriched to provide new scholarship and insights on The Met collection.

“About.” The Heilbrunn Timeline

It is important to note that the way in which the authors conceived of and approach this timeline is through the works in the Met’s collection. While there are some works of art and artists discussed in the Timeline that are not present in the Met’s collection, I think this is an important aspect to note as it could hide potential biases; if they are only writing about works that are in their collection, what is left out from this “global” timeline? Are there art objects underrepresented at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? This immediately called to mind one of the works by the Guerilla Girls which called attention the lack of diversity in the Met’s collection.

While there certainly have been vast improvement in the diversity of the collection from the time that this piece was made, it is important to remember to always interrogate the resources that we utilize, especially if they are new(er) resources as oftentimes the “shiny” factor of a new digital technology can outshine some inherent biases in the resource. I do not mean to be overly critical of the Heilbrunn Timeline- I have used it in my work as a jumping point for my research many times; I just wanted to shine light on one of the issues in creating a “global art history timeline” that only uses (primarily or otherwise) the works in one museum. Though, it is clear that the timeline is truly focusing on the items in the “Met Collection,” as it is clearly stated twice in the opening paragraph in the “About” section.

The digital resource is primarily divided into four different sections:

The Timeline is structured with four components. Essays focus on specific themes in art history, including artistic movements and periods, archaeological sites, empires and civilizations, recurrent themes and concepts, media, and artists. Works of Art celebrate human creativity from around the world and from all eras, and are contextualized chronologically, geographically, and thematically. Chronologies provide a linear outline of art history by geographical region. Each chronology includes up to ten representative works of art, a timeline, an overview, and key events. Keywords—categorized by art movement and style, artists and makers, geography (present-day nation states and historical regions), time period, material and technique, object, and subject matter—further connect chronologies, essays, and works of art.

“About.” The Heilbrunn Timeline

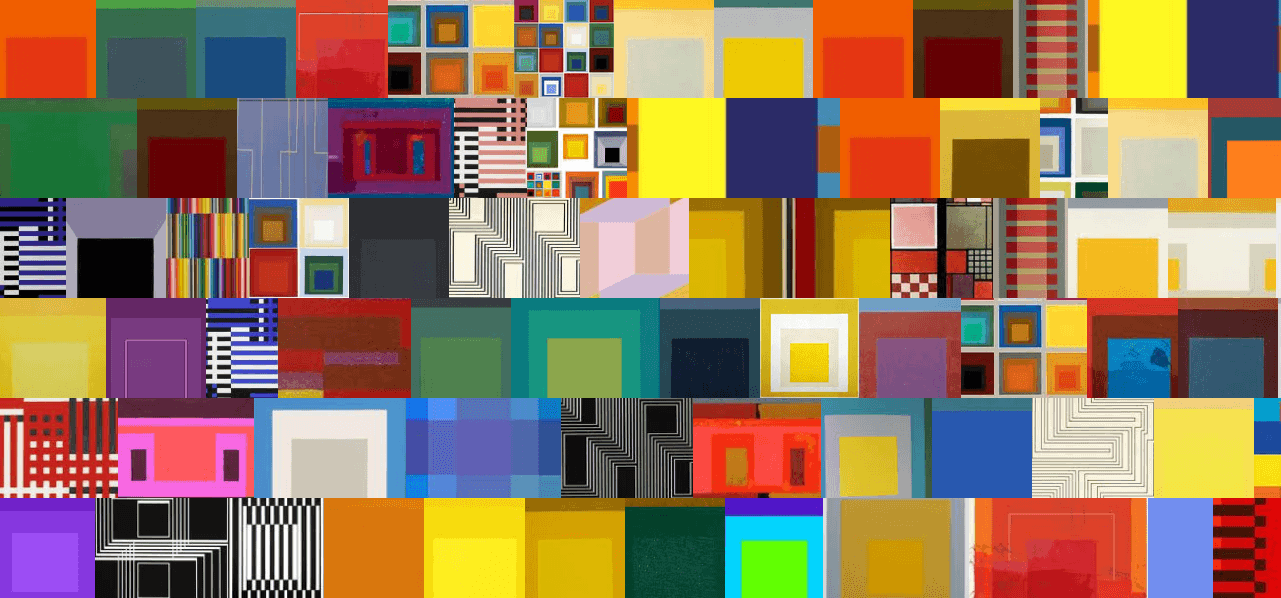

When looking at the front page of the Timeline, you can choose three different options, Essays, Works of Art, and Chronologies, each of which will bring you to its own unique home page. One of the interesting facets of this tool, for me, is the way in which each section incorporates chronology or some sense of time in each of the individual menus.

Of all the sections, the “Chronology” section most embodies the mapping time and space that we have looked at this past week.

Through this tool, you can mouse over a geographic area to specify which timeline you might be interested in browsing, or you can scroll through the 291 timelines (just as you can scroll through the over one thousand essays). After choosing a specific timeline or essay, one of the additional resources that I find particularly useful is the inclusion of a bibliography or further reading section, which is great if you are using the Heilbrunn Timeline as an initial resource from which you can jump to more in depth resources. Additionally, all of the works mentioned in the essays or timelines are linked to the object in the Met’s collection (which is now open access if the object is in the public domain!!). Overall, definitely a great resource and example of a complex art historical timeline that maps not only geography but also time.

Timelines & Me

As always, we were able to play around with some tools in class: TimeMapper and TimelineJS. These two are extremely similar with the main difference being TimeMapper includes a geographic map in addition to the timeline. Both utilize a Google Sheets as the template in which you place the data and overall, is quite easy to use.

For my timeline, I wanted to create a timeline that would be useful for me to use in my own research, so I decided to focus it on my topic of my art history master’s thesis. To give an (extremely brief!) overview, I am looking at Tom Phillips’ canonical artist’s book A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel in relation to Phillips interest in ornament, an area that has been neglected in scholarship on Phillips. In this timeline, I wanted to interweave the publication of various prominent theories of ornament into a timeline on Phillips’ work. While certainly not comprehensive (of Phillips’ history not the entire historiography of theories of ornament), it is an interesting visual to include in my research and the process of creating the timeline made be look at some connections that I had not thought of yet, such as the fact that Robert Venturi was publishing his work while Phillips was at Oxford and he could have encountered the ideas then. Below is the link to my timeline: let me know what you think!

In case the embed isn’t working, here is a link to my timeline.